You’ve probably never heard of Leonardo Bonacci; that’s because nowadays he is known by a fake name given him by a French historian in 1838, six hundred years after Leonardo died: Fibonacci. Nowadays, he is best known for Fibonacci numbers, which describe the layout of certain spirals. Big deal. Bonacci’s true contribution to Western civilization is far more important than any stupid spirals: he gave us access to arithmetic.

Bonacci was the son of a wealthy Italian merchant who ran the trading post for Pisa in a seaport in North Africa. Here, Italian and Islamic merchants did their business. He often acted as an agent for his father in trips around the coast of North Africa, negotiating directly with the Islamic merchants. To do so, he had to familiarize himself with the commercial practices of the Islamic merchants: their special financial tools for working around the Islamic prohibition on interest, their language, and the strange numerals that they had learned from the Hindus: 0, 1, 2, 3....

Christendom in those times (about 1200 CE) was using Roman numerals. This system was clumsy, slow, and useless for arithmetic. Consider, for example, this simple addition problem:

Pretty hard, isn’t it? You really can’t do it without translating the Roman numbers into Arabic form, doing the addition, and translating back, can you? Can you imagine how hard multiplication and division must have been? This discouraged use of even simple arithmetic.

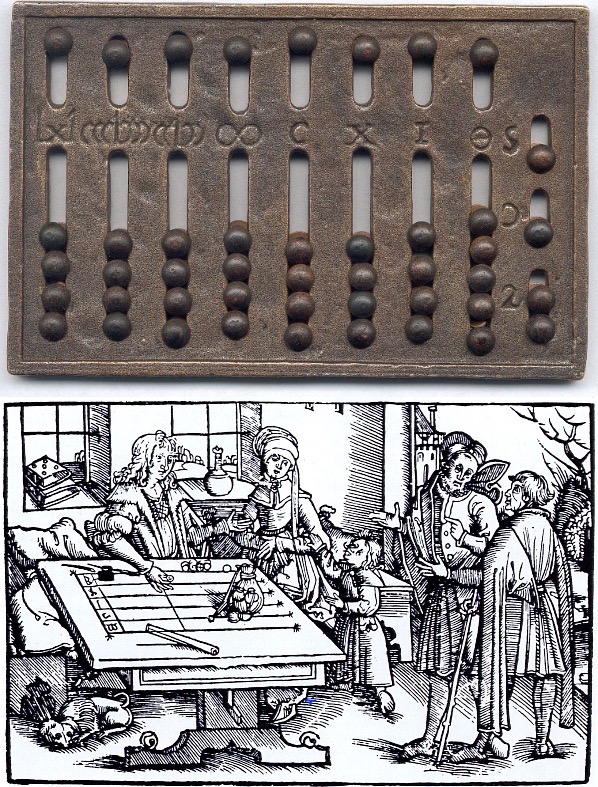

Instead, they used a simple device called a “counting board”. The upper image shows a modern rendition while the lower image shows one in use:

You could carry out simple addition and subtraction just by moving beads around on the counting board. The Chinese had a much better version of the same concept, which we now call an abacus.

The weaknesses of Roman numerals wasn’t much of a problem in Christendom, because nobody really needed to do much with numbers than record them. The written records people kept in those days required little more than the year and various static numbers: taxes paid, number of people, soldiers, cattle, villages, and so forth.

Arithmetic was unnecessary for such usages. So Christians continued using Roman numerals.

This was all well and good for simple matters, but trade between Christians and Muslims elevated an old problem to much more serious levels: how do you convert between currencies? How do you convert XCV Genoese grossos into dinars? This requires multiplication or division — which are all but impossible to carry out with Roman numerals. The Islamic merchants had already been dealing with such problems for centuries, and they had learned that the only way to carry out such calculations used the Hindu numerals.

So Bonacci learned this new system of numbers, and later in life, back in Italy, he wrote a book about how the system worked: Liber Abaci (Book of Calculation). The response was mixed. At first, only some merchants showed interest in the new system, especially those already trading with Islamic merchants. There was certainly some resistance from people who refused to learn the new system and thought that it was some sort of conspiracy to cheat them. In 1299 Florence issued an edict forbidding bankers to use the Hindu-Arabic numerals, largely because sharp operators were using the Arabic numerals to cheat people who weren’t familiar with the new system. However, the benefits of the new system were so great that the ban was later rescinded.

At a deeper level, quantification was seeping into European consciousness. Monks prayed at standard times called the canonical hours. But how were they to know the proper time for their prayers? They needed clocks. Initially they used water clocks or candles that burned at a regular rate, but these clocks were unreliable; candles burnt out and water clocks sometimes froze. Something better was needed. The first mechanical clocks were large affairs mounted on towers; they rang bells on the hours, informing all the monks of the time. The commoners quickly realized just how useful these were for regulating working hours that towns all over Europe began installing their own clock towers. Time was no longer something that merely slipped by; it was now measured by the hour. Scales of different sizes were increasingly used to measure the quantity of goods being sold. Some products were measured by length; some by volume. Bit by bit, numbers played an increasingly important role in European civilization, to a degree well beyond that of any other civilization.

Over the next few centuries, the “Arabic” numerals spread throughout the financial system. By 1478 the system was so common that a standard textbook on arithmetic using Arabic numerals, the Treviso Arithmetic, was published. It became the standard textbook for arithmetic and was a required component of education of every young merchant. From there it spread into astrology/astronomy (There was no distinction between the two back then.) Galileo used Arabic numerals in his works, and from there they became standard throughout Christendom.